It is a great privilege to be invited to write the foreword of a book. I feel honored and humbled by Mary Gaetjens’s request to do so for Anse-à-Vodou: A summer with my father in Haiti, the fruit of her many years of passionate dedication, compassionate vision, and tireless study and research.

My wife Nancy and I had the pleasure of meeting Mary in the mid 1980s, while she was in college in Philadelphia, when our dear and regrettably lost friend, her father, Gérard, to whom the book is dedicated, came to our home especially to introduce her. A most affectionate friendship resulted from that introduction, and since then, Mary and our family have remained close. We also vividly remember her visit a few years later to present her future husband, Paul. Since their move to California, we have constantly remained in touch.

I knew Gérard Gaetjens as well as several other members of the family, particularly his brothers Joe and Jean, since the 1950s, when all of us were alive and happy in Haiti. Sadly enough, murderous Haitian dictators were responsible for the untimely death of Gérard and Joe, and the forced exile of Jean. In the book, Mary places her father’s departure from Haiti in 1964. Before coming to the United States and settling in Boston, he spent some time in the Dominican Republic. When he relocated to New York, we became involved with several Haitian militant opposition groups fighting to free Haiti. We also shared a deep interest in Haiti’s history and culture, particularly our native African religious heritage, Haitian Vodou. Upon Gérard’s return to Haiti in 1986 after the overthrow of Jean-Claude Duvalier, he remained active in the struggle for freedom in Haiti until his assassination on August 29, 1990, by cowardly death squads of a neo-Duvalierist movement.

Jean, Gérard’s younger brother, also became a close friend of mine. As a naval officer in Haiti in the mid 1950s, I was a member of an examination committee that selected him from among several other candidates as beneficiary of a scholarship to study at Cuba’s Naval Academy. In addition to his meritorious scholarly distinction, Jean proved that he was also a proud patriot ready to sacrifice a promising career to defend the honor of his country. While he was a cadet at the Academia Naval de Cuba, agents of President Fulgencio Batista violated the Embassy of Haiti in order to kidnap some Cuban citizens who had taken refuge there. In protest against that vile insult to his country, Jean immediately surrendered his uniform to the Academia Naval and returned to Haiti. This noble and patriotic gesture led to Haitian President Paul Eugène Magloire’s decision to award to him the diploma and commission ofaiti Enseigne de Vaisseau (Lieutenant). Jean stayed for several years as an officer of the Garde-Côtes d’Haïti (Haitian Coast Guard), but after President Magloire’s departure and the fraudulent elections of 1957, he refused to serve François Duvalier and promptly left the country. A very smart decision indeed; otherwise, he would have surely been assassinated. While in exile, Jean was continuously active in the fight against the dictatorship.

Gérard’s older brother Joe Gaetjens is the world-famous soccer player who gave the United States its phenomenal World Cup victory against England on June 29, 1950. People in the United States, Haiti, and the whole world celebrated his triumph. Joe’s son Lesly writes about that memorable event: “Out of nowhere apparently, my father came and went head first and hit the ball hard enough to change its direction – so the goalie from the England team was going one way and the ball went the other way.”

Although not involved in politics or opposition movements, Joe, a national and international celebrity, was cravenly murdered by François Duvalier himself. Mary describes the climate that prevailed in Haiti in those times and the circumstances that accompanied Joe’s death: “Duvalier’s Tonton Makout … disappeared many tens of thousands of people…. Gérard’s brother Joe was one of them, a statistic. No one wanted to face the rumors that he was dead, not yet. Joe had refused to flee Haiti even though their brother Jean was openly plotting against Duvalier in the Dominican Republic. When their youngest brother, Fred, returned from prison, swollen, broken, and covered in blood, and immediately left Haiti to join Jean, Joe still refused to go, saying his brothers’ plan had nothing to do with him. He refused Gérard’s desperate pleas to flee for his safety, believing that being a national hero dressed him in armor impermeable to politics.”

Although not born in Haiti, Mary has inherited from her father, her uncles, and the Gaetjens family a deep attachment and devotion to all matters Haitian. To her father, a scholar in his own right in the religious traditions and beliefs of the country, she owes her particular interest in Haitian Vodou. When I asked about her motivation to pursue research in the field, she answered that it was the inspiration and guidance he had provided.

Mary began research for her book in 1989 during her first visit to Haiti. She was determined to spend as much time as possible in various Lakou, among them one in Anse-à-Veau, the region whose name inspired the title of the book. She was there in the summer of 1989 during the festivities for Ogoun and spent time with the Gesner Saint Cyr family. She did not neglect to visit Souvnans, Soukri, and Badjo, the three most important and oldest Lakou of the country, all founded in the 1700s, before Haiti’s independence. At Souvnans she met the ///Lakou‘s sèvitè///I’m uneasy about changing GF’s words without asking him. ??///, I asked him, but I’m sure I’m right and he went off of what I wrote in the book. Ati Bien-Aimé; she returned during the 2013 festival time and stayed a week. She visited Soukri again in the summer of 2016, stayed a week, and had brief conversations with Aboudja, the Emperor of Soukri, and Dr. Grégoire Diiéguélé-Matsua, a Haitian ethnographer from Africa and now the principal manifestation of the lwa Zinga at Soukri. She went to Badjo outside of festival time in 1989, but she had the opportunity to greet the temple and salute the manbo. Mary’s studies in spirituality have led her on several other journeys, to Mexico, Brazil, India, Ireland, and most recently Colombia.

Mary showed the first draft of the book to her father in the summer of 1990. It was very different from today’s publication. She told me it was a young Western woman’s viewpoint of a culture from personal experience of Vodou ceremonies, and the feeling of homecoming she had with a lwa and a gede. He advised her to be more specific about what she had seen and explain it in more detail. In a personal note, Mary told me frankly that she did not like his advice but over the years she came to agree, and after his passing, which was crushing for her, she wrote intermittently, using writing as a healing modality to process his death.

Alongside works published by famous authors like Milo Marcelin, Louis Maximilien, Alfred Métraux, Jean Price-Mars, Milo Rigaud, and others, Anse-à-Vodou: A summer with my father in Haiti will contribute to the defense and illustration of our ancestral religion. It will help dispel the erroneous ideas held by some that Vodou is a cult involving malefic rituals, witchcraft, secret ceremonies, mysterious deaths, bloody sacrifices, and similar false descriptions often invented and exploited by dishonest writers in search of gaudy sensationalism.

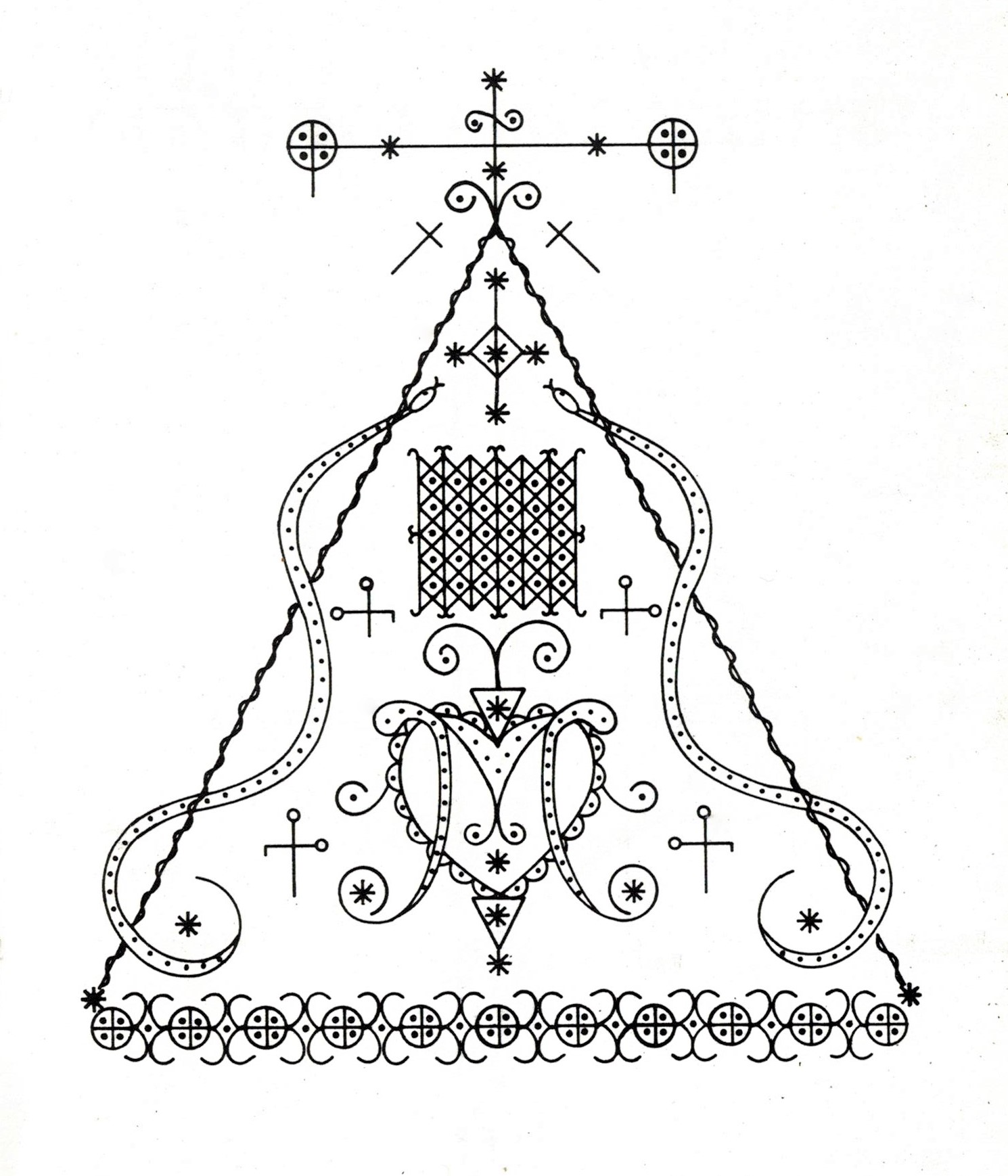

Readers of Anse-à-Vodou will understand that Haitian Vodou is in part a religion which, like all others, has its beliefs, its pantheon of supernatural beings that includes one Supreme God, the Gran Mèt, under whom are placed divinities called lwa, gede, espri, zanj. It has its temples and clergy of houngan, manbo, hounsi, its congregation, rites, all the paraphernalia found in religions. Its goal is to honor its spiritual entities from whom the followers ask, to quote author Alfred Métraux, “what men have always asked of religion: remedy for ills, satisfaction for needs and the hope of survival”. A great proportion of the Haitian population lives in constant, though perhaps subconscious, anxiety. The rural population and urban proletariat have difficulty securing and holding land rights and are often victims of crop failures or natural disasters. They and their loved ones are subject to numerous devastating diseases with no hope for medical treatment, except that offered by the houngan, the manbo, or the doktè fèy, the herbalist.

Haitian Vodou is not only a religion, it is also tradition, family and social lifestyle, leisure, folklore, music, dance, theater, visual art, and more. Haitian writer Jacques Stephen Alexis calls it “l’âme du peuple”, the soul of the people. It provides its devotees with a unique and indispensable resource at their disposal to salvage their mental sanity, physical health and social happiness. Worship of the divinities offers recourse and relief, some feeling of control over their spiritual and physical environment.

Mary weaves her nascent understanding of Vodou into a compelling and heart-expanding narrative of Haitian history, family history, and her own spiritual development. Anse-à-Vodou: A summer with my father in Haiti is destined to become one of the great classics of Haitian Vodou’s religious and ethnographic literature, along with the exceptional artistic and esthetic character of its photographs.

Professor Emeritus, Saint Joseph’s University, Author of Le Vodou Haïtien sans mystification